The suggestion that you can plant trees to offset your carbon emissions is widespread. Many businesses, from those selling shoes to booze, now offer to plant a tree with each purchase, and more than 60 countries have signed up to the Bonn Challenge, which aims to restore degraded and deforested landscapes.

However, expanding tree cover could affect the climate in complex ways. Using models of the Earth’s atmosphere, land and oceans, we have simulated widescale future forestation. Our new study shows that this increases atmospheric carbon dioxide removal, beneficial for tackling climate change. But side-effects, including changes to other greenhouse gases and the reflectivity of the land surface, may partially oppose this.

Our findings suggest that while forestation – the restoration and expansion of forests – can play a role in tackling climate change, its potential may be smaller than previously thought.

When forestation occurs alongside other climate change mitigation strategies, such as reducing emissions of greenhouse gases, the negative side-effects have a smaller impact. So, forestation will be more effective as part of wider efforts to pursue sustainable development. Trees can help fight climate change, but relying on them alone won’t be enough.

What does the future hold?

Future climate projections suggest that to keep warming below the Paris Agreement 2°C target, greenhouse gas emissions must reach net-zero by the mid-to-late 21st century, and become net negative thereafter. As some industries, such as aviation and shipping, will be exceedingly difficult to decarbonise fully, carbon removal will be needed.

Forestation is a widely proposed strategy for carbon removal. If deployed sustainably – by planting mixtures of native trees rather than monocultures, for instance – forestation can provide other benefits including protecting biodiversity, reducing soil erosion, and improving flood protection.

We considered an “extensive forestation” strategy which expands existing forests over the course of the 21st century in line with current proposals, adding trees where they are expected to thrive while avoiding croplands.

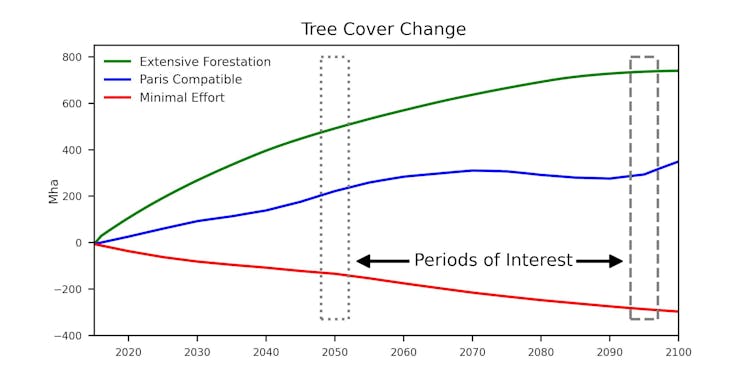

In our models, we paired this strategy with two future climate scenarios – a “minimal effort” scenario with average global warming exceeding 4°C, and a “Paris-compatible” scenario with extensive climate mitigation efforts. We could then compare the extensive forestation outcome to simulations with the same climate but where levels of forestation followed more expected trends: the minimal effort scenario sees forest cover drop as agriculture expands, and the Paris-compatible scenario features modest increases in global forest cover.

Change in forest cover relative to 2015 in the three land cover scenarios considered. Our study focused our analysis on the periods around 2050 and 2095. Author provided, Author provided (no reuse)

Up in the air

The Earth’s energy balance depends on the energy coming in from the Sun and the energy escaping back out to space. Increasing forest cover changes the Earth’s overall energy balance. Generally, changes that decrease outgoing radiation cause warming. The greenhouse effect works this way, as outgoing radiation is trapped by gases in the atmosphere.

Forestation’s ability to lower atmospheric CO₂, and therefore increase the radiation escaping to space, has been well studied. However, the amount of carbon that could feasibly be removed remains a subject of debate.

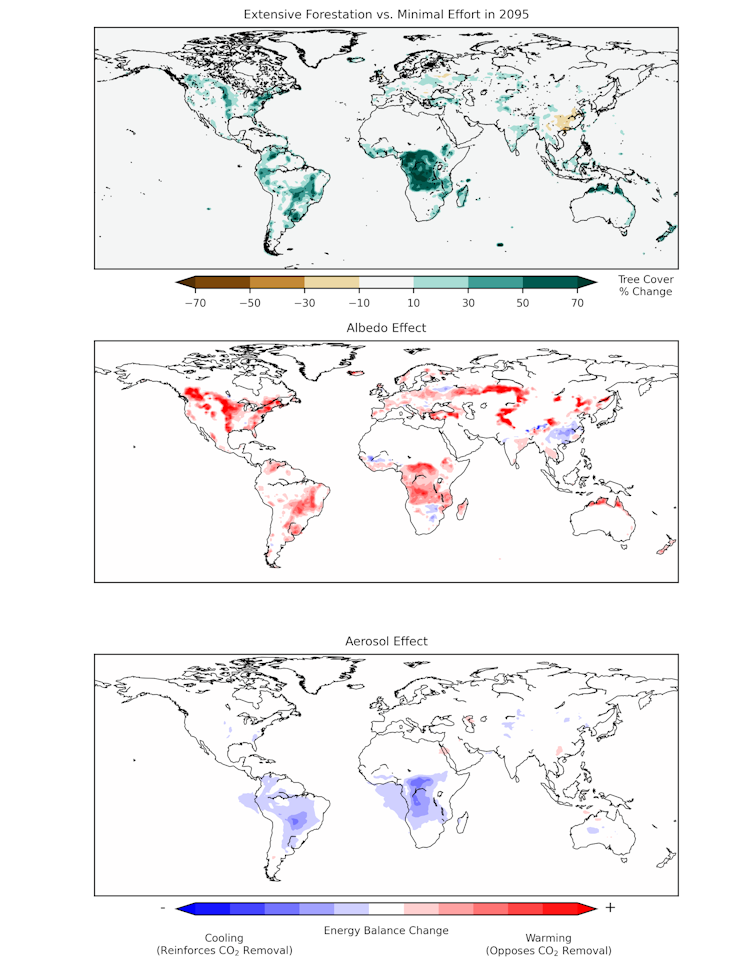

Forestation generally reduces land surface reflectivity (albedo) as darker trees replace lighter grassland. Decreases in albedo levels oppose the beneficial reduction of atmospheric CO₂, as less radiation escapes back to space. This is particularly important at higher latitudes, where trees cover land that would otherwise be covered with snow. Our scenario features forest expansion primarily in temperate and tropical regions.

Forests emit large quantities of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), with these emissions increasing with rising temperatures. VOCs react chemically in the atmosphere, affecting the concentrations of methane and ozone, which are also greenhouse gases. We find the enhanced VOC emissions from greater forest cover and temperatures increase levels of methane and, typically, ozone. This reduces the amount of radiation escaping to space, further opposing the removal of carbon.

However, the reaction products of VOCs can contribute to aerosols, which reflect incoming solar radiation and help form clouds. Increases in these aerosols with rising VOC emissions from greater forest cover result in more radiation escaping to space.

We find the net effect of changes to albedo, ozone, methane and aerosol is to reduce the amount of radiation escaping to space, cancelling out part of the benefit of reducing atmospheric CO₂. In a future where climate mitigation is not a priority, up to 30% of the benefit is cancelled out, while in a Paris-compatible future, this drops to 15%.

Top: Difference in tree cover between extensive forestation and minimal effort scenarios at 2095. Effect on energy balance due to the forest cover differences from albedo change (Middle) and aerosol change (Bottom). Red indicates a net increase in energy balance (warming) and blue a net decrease (cooling).

Cooler solutions

Tackling climate change requires efforts from all sectors. While forestation will play a role, our work shows that its benefits may not be as great as previously thought. However, these negative side-effects aren’t as impactful if we pursue other strategies, especially reducing our greenhouse gas emissions, alongside forestation.

This study hasn’t considered local temperature changes from forestation as a result of evaporative cooling, or the impact of changes to atmospheric composition caused by changes in the frequencies and severities of wildfires. Further work in these areas will complement our research.

Nevertheless, our study suggests that forestation alone is unlikely to fix our warming planet. We need to rapidly reduce our emissions while enhancing the ability of the natural world to store carbon. It is important to stress-test climate mitigation strategies in detail, because so many complex systems are at play.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 30,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Before you go …

90,000 experts have written for The Conversation. Because our only agenda is to rebuild trust and serve the public by making knowledge available to everyone rather than a select few. Now, you can receive a curated list of articles in your inbox twice a week. Give it a go?

Jo Adetunji

Editor, The Conversation UK

James Weber

Lecturer in Atmospheric Radiation, Composition and Climate, University of Reading

James A. King

Research Associate in Climate Change Mitigation, University of Sheffield

Disclosure statement

James Weber receives funding from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

James A. King sits on an advisory panel for Ecologi. He receives funding from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

Comments

Post a Comment